Apache HTTP Server Version 2.2

Apache HTTP Server Version 2.2

This document refers to a legacy release (2.2) of Apache httpd. The active release (2.4) is documented here. If you have not already upgraded, please follow this link for more information.

You may follow this link to go to the current version of this document.

This document supplements the mod_rewrite

reference documentation. It

describes the basic concepts necessary for use of

mod_rewrite. Other documents go into greater detail,

but this doc should help the beginner get their feet wet.

Introduction

Introduction Regular Expressions

Regular Expressions RewriteRule Basics

RewriteRule Basics Rewrite Flags

Rewrite Flags Rewrite Conditions

Rewrite Conditions Rewrite maps

Rewrite maps .htaccess files

.htaccess filesThe Apache module mod_rewrite is a very powerful and

sophisticated module which provides a way to do URL manipulations. With

it, you can do nearly all types of URL rewriting that you may need. It

is, however, somewhat complex, and may be intimidating to the beginner.

There is also a tendency to treat rewrite rules as magic incantation,

using them without actually understanding what they do.

This document attempts to give sufficient background so that what follows is understood, rather than just copied blindly.

Remember that many common URL-manipulation tasks don't require the

full power and complexity of mod_rewrite. For simple

tasks, see mod_alias and the documentation

on mapping URLs to the

filesystem.

Finally, before proceeding, be sure to configure

mod_rewrite's log level to one of the trace levels using

the LogLevel directive. Although this

can give an overwhelming amount of information, it is indispensable in

debugging problems with mod_rewrite configuration, since

it will tell you exactly how each rule is processed.

mod_rewrite uses the Perl Compatible Regular Expression vocabulary. In this document, we do not attempt to provide a detailed reference to regular expressions. For that, we recommend the PCRE man pages, the Perl regular expression man page, and Mastering Regular Expressions, by Jeffrey Friedl.

In this document, we attempt to provide enough of a regex vocabulary

to get you started, without being overwhelming, in the hope that

RewriteRules will be scientific

formulae, rather than magical incantations.

The following are the minimal building blocks you will need, in order

to write regular expressions and RewriteRules. They certainly do not

represent a complete regular expression vocabulary, but they are a good

place to start, and should help you read basic regular expressions, as

well as write your own.

| Character | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

. | Matches any single character | c.t will match cat,

cot, cut, etc. |

+ | Repeats the previous match one or more times | a+ matches a, aa,

aaa, etc |

* | Repeats the previous match zero or more times. | a* matches all the same things

a+ matches, but will also match an empty string. |

? | Makes the match optional. |

colou?r will match color and colour. |

^ | Called an anchor, matches the beginning of the string | ^a matches a string that begins with

a |

$ | The other anchor, this matches the end of the string. | a$ matches a string that ends with

a. |

( ) | Groups several characters into a single unit, and captures a match for use in a backreference. | (ab)+

matches ababab - that is, the + applies to the group.

For more on backreferences see below. |

[ ] | A character class - matches one of the characters | c[uoa]t matches cut,

cot or cat. |

[^ ] | Negative character class - matches any character not specified | c[^/]t matches cat or c=t but not c/t |

In mod_rewrite the ! character can be

used before a regular expression to negate it. This is, a string will

be considered to have matched only if it does not match the rest of

the expression.

One important thing here has to be remembered: Whenever you

use parentheses in Pattern or in one of the

CondPattern, back-references are internally created

which can be used with the strings $N and

%N (see below). These are available for creating

the strings Substitution and TestString as

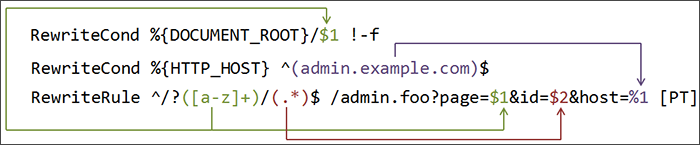

outlined in the following chapters. Figure 1 shows to which

locations the back-references are transferred for expansion as

well as illustrating the flow of the RewriteRule, RewriteCond

matching. In the next chapters, we will be exploring how to use

these back-references, so do not fret if it seems a bit alien

to you at first.

Figure 1: The back-reference flow through a rule.

In this example, a request for /test/1234 would be transformed into /admin.foo?page=test&id=1234&host=admin.example.com.

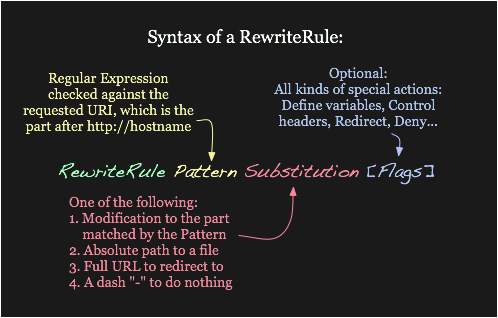

A RewriteRule consists

of three arguments separated by spaces. The arguments are

The Pattern is a regular expression. It is initially (for the first rewrite rule or until a substitution occurs) matched against the URL-path of the incoming request (the part after the hostname but before any question mark indicating the beginning of a query string) or, in per-directory context, against the request's path relative to the directory for which the rule is defined. Once a substitution has occurred, the rules that follow are matched against the substituted value.

Figure 2: Syntax of the RewriteRule directive.

The Substitution can itself be one of three things:

RewriteRule ^/games.* /usr/local/games/web

This maps a request to an arbitrary location on your filesystem, much

like the Alias directive.

RewriteRule ^/foo$ /bar

If DocumentRoot is set

to /usr/local/apache2/htdocs, then this directive would

map requests for http://example.com/foo to the

path /usr/local/apache2/htdocs/bar.

RewriteRule ^/product/view$ http://site2.example.com/seeproduct.html [R]

This tells the client to make a new request for the specified URL.

The Substitution can also contain back-references to parts of the incoming URL-path matched by the Pattern. Consider the following:

RewriteRule ^/product/(.*)/view$ /var/web/productdb/$1

The variable $1 will be replaced with whatever text

was matched by the expression inside the parenthesis in

the Pattern. For example, a request

for http://example.com/product/r14df/view will be mapped

to the path /var/web/productdb/r14df.

If there is more than one expression in parenthesis, they are

available in order in the

variables $1, $2, $3, and so

on.

The behavior of a RewriteRule can be modified by the

application of one or more flags to the end of the rule. For example, the

matching behavior of a rule can be made case-insensitive by the

application of the [NC] flag:

RewriteRule ^puppy.html smalldog.html [NC]

For more details on the available flags, their meanings, and examples, see the Rewrite Flags document.

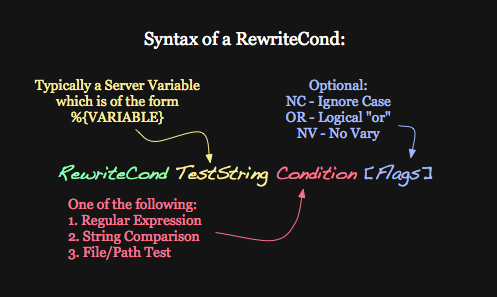

One or more RewriteCond

directives can be used to restrict the types of requests that will be

subject to the

following RewriteRule. The

first argument is a variable describing a characteristic of the

request, the second argument is a regular

expression that must match the variable, and a third optional

argument is a list of flags that modify how the match is evaluated.

Figure 3: Syntax of the RewriteCond directive

For example, to send all requests from a particular IP range to a different server, you could use:

RewriteCond %{REMOTE_ADDR} ^10\.2\.

RewriteRule (.*) http://intranet.example.com$1

When more than

one RewriteCond is

specified, they must all match for

the RewriteRule to be

applied. For example, to deny requests that contain the word "hack" in

their query string, unless they also contain a cookie containing

the word "go", you could use:

RewriteCond %{QUERY_STRING} hack

RewriteCond %{HTTP_COOKIE} !go

RewriteRule .* - [F]

Notice that the exclamation mark specifies a negative match, so the rule is only applied if the cookie does not contain "go".

Matches in the regular expressions contained in

the RewriteConds can be

used as part of the Substitution in

the RewriteRule using the

variables %1, %2, etc. For example, this

will direct the request to a different directory depending on the

hostname used to access the site:

RewriteCond %{HTTP_HOST} (.*)

RewriteRule ^/(.*) /sites/%1/$1

If the request was for http://example.com/foo/bar,

then %1 would contain example.com

and $1 would contain foo/bar.

The RewriteMap directive

provides a way to call an external function, so to speak, to do your

rewriting for you. This is discussed in greater detail in the RewriteMap supplementary documentation.

Rewriting is typically configured in the main server configuration

setting (outside any <Directory> section) or

inside <VirtualHost>

containers. This is the easiest way to do rewriting and is

recommended. It is possible, however, to do rewriting

inside <Directory>

sections or .htaccess

files at the expense of some additional complexity. This technique

is called per-directory rewrites.

The main difference with per-server rewrites is that the path

prefix of the directory containing the .htaccess file is

stripped before matching in

the RewriteRule. In addition, the RewriteBase should be used to assure the request is properly mapped.